Three years after missing the nostalgia train, Grand Theft Auto's definitive editions has silently delivered its defining statement - for consoles, rather than Netflix

A rollout as protracted as its title ends with an inevitable reversion.

Grand Theft Auto III is the defining title of its generation. Within the industry, irrespective of genre nor audience, all that came before Rockstar’s celestial triumph should be measured in terms of its years removed from GTA III; the unbridled verve of its metropolis delivered cinematic scope with gleeful abandon. Revisiting the game on advanced hardware illuminates its inherent antiquities and quirks, though not to the detriment of its solemn blue horizons and uniformly grey cityscape - CRT-noir with the texture of a mob potboiler of yore. To honour its twentieth anniversary, Rockstar announced a compilation of its inaugural trilogy, comprised of III and its successors in Vice City and San Andreas. A conspicuously vague announcement trailer aroused interest from its promise alone, purportedly designed to refute the cynicism associated with the public perception of contemporary Rockstar and its parent company in Take-Two Interactive. How could Rockstar disrespect these totemic emblems of their empire?

Regrettably, the answer to the above emerged as “quite easy!” Converted to Unreal Engine 4 from their original RenderWare engine, the distinctive character of each game was systematically stripped apart; the developers in Grove Street Games infamously resorted to AI to recreate particular textures, eventuating in curious typos. Additionally, each of the titles were plagued by outrageous glitches, rendering an otherwise perfunctory experience fundamentally broken. Rockstar’s decision to strip the original PC ports from online storefronts - save for a purchase of this collection for a limited time - served as a fine dash of salt to their PR wound; their own internal project failed to respect their games on a tantamount scale to their respective modding communities. Owners of the original port of Vice City were treated to a Back to the Future-themed conversion with a functional DeLorean; Vice City’s definitive edition hardly approximated its vanilla aesthetic.

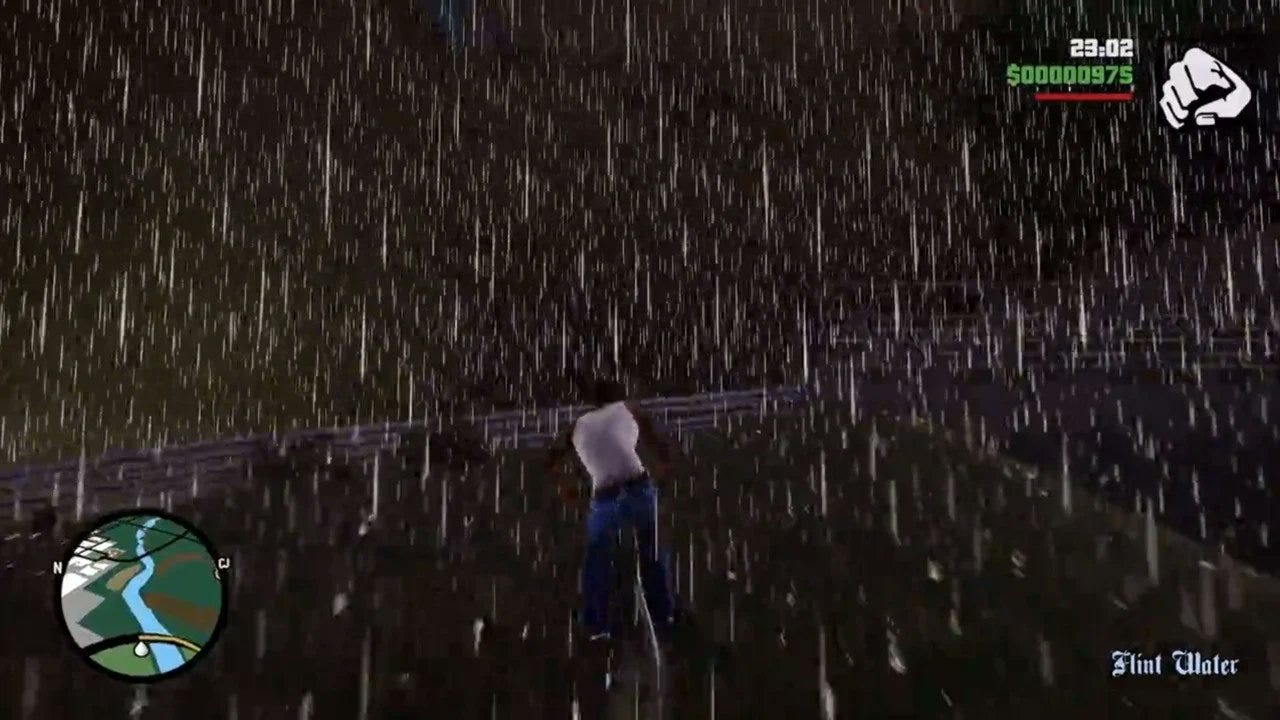

In the intervening years, Grove Street Games were deposed by Rockstar: an ignominious end to their tenure upon their namesake. Though its stability increased with each patch, the pervasive air of cynicism congested its critical estimation, though its commercial success - to the tune of 14 million sales - was a triumph in asserting the validity of the minimum viable product model. Regarding its revisions, the team implemented a radio wheel in the manner of Grand Theft Auto V, whilst modernising the aiming scheme. Character models, however, were stranded in an uncanny valley: their plasticine composition failed to evoke the iconography of its inspirator, instead rendering them as awkwardly mannered dolls. Furthermore, its initial depiction of rain oddly obfuscated the screen, momentarily masking its flattened palette.

It never rains in Southern California - it pours enough to make your game inscrutable.

In a curious case of corporate coercion, Netflix allowed subscribers to access the mobile edition of the trilogy through their phones - two years removed from its formal debut. That Netflix made a play for a depreciated, yet coveted commodity in these definitive editions seemed to be both a surrender and a savvy spin on Rockstar’s behalf: lowering expectations to the most minimal barrier of entry conceivable. However, its second mobilisation conquered critics with the addition of a “classic lighting” feature, returning the colour coordination lost to Grove Street Games’ original interpretation. Thus, one could experience San Andreas with its iconic orange hues and blistering blues, approximating the impressionism lost to time. Vice City, conversely, earned the courage of its ident, adorning itself in pink and teal with great zeal.

Rockstar parted from their vices to deliver a surprisingly sound mobile experience.

Nevertheless, consoles would not receive this thorough makeover for eleven months. Earlier this week, Rockstar patched both PC and next-generation consoles to allow owners to enable “classic lighting”; the Switch and their last-generation kin followed suit. On a canvas wider than a smartphone, Rockstar’s alterations shone through anew; the mellifluous harmony between one’s ride and Vice City’s vistas captured the precise centre of nostalgic revelry. At last, a first-party reprisal of their signature stories bore honest aesthetic qualities, rather than mimicking them through an impressive, if not sparse fan render via the Unreal Engine.

Courtesy of @BeskInfinity, a direct comparison of vantage points from the original release to the latest edition.

Indeed, this trilogy is a relic of a bygone era, wherein developers were challenged to contend against tightened technical limitations. Drawing upon the principles of GTA V in reanimating them for the (more) modern day represented a rare conceptual failure from the studio, both in outsourcing its design and reverting upon its distance. On release, this definitive package was delivered as a wooden table without lacquer: its edges were sharpened, yet its finish was lacking. Though it is not without flaw, particularly in its basis of direct translation, rather than faithful interpretation, blasting Flash FM as the sun sets upon the horizon remains one of the medium’s most ecstatic joys.