How Lego James Bond had its license killed - or, the covert cancellations that were later declassified

From datamines to miraculous finds, a web of corporate conniving awaits.

When you read the name James Bond, two soundbites likely pass through your mind. First, your generation’s iteration introducing himself as Bond, James Bond, who prefers his martinis shaken, rather than stirred - save for Daniel Craig. Then, you would hear a familiar dun-da-dun, though its notoriety may have been surpassed by GoldenEye 64’s prescient pause theme. Regardless, a series of this esteem, bearing the most memorable motifs of the medium, is a totemic vessel of merchandising; two of the gaming industry’s most prominent players in Electronic Arts and Activision alone delivered a combined fifteen titles featuring the character.

Unfortunately, none of their efforts quite seized the zeitgeist as firmly as the aforementioned GoldenEye, though GoldenEye: Rogue Agent boasted Silent Hill’s CGI cutscene director in Takayoshi Sato as its character designer. Their foremost folly, however, was in their broad conception as first-person shooters, rather than espionage jaunts with puzzles and poker. However, after lying dormant for four years following 007 Legends - a calamity that collapsed its developer in Eurocom and caused Activision to forfeit their license - Traveller’s Tales reportedly pitched a virtual Lego adaptation of the franchise; this was their solution to Lego Dimensions’ dwindling fortunes.

The double entendre of “stud” alone would make for ample comedic material.

Despite their most whimsical efforts, The Lego Group reportedly refuted their ambition, citing the series’ violence and innuendo as antithetical to the family-friendly form of their brand. Unfortunately, reducing Bond to a plastic model does not solve his inherent sexual overtones, affinity for alcohol, or the title of the 1983 film Octopussy. Attempting to render Connery’s films palatable for younger players would be a significantly greater feat than translating Indiana Jones - particularly in conveying his licence to kill as definitively lethal, rather than permission to dissassemble. Regardless, it is amusing to imagine the awkward conversations between the team and the Lego Group, trying to justify featuring characters named Pussy Galore and Holly Goodhead. Still, one can imagine its success to be predicated on cultural osmosis; his signature style, theme, and setpieces could be delivered with sanitised precision.

Similarly, a library of lost titles have emerged from their cancellation chrysalis; their fates were determined by powers outside of the consumer’s purview. Infamously, the Star Wars series has a pair of promising pitches in Battlefront III and 1313 that were placed on carbonite following Disney’s acquisition of Lucasfilm: the former can be accessed via emulation, whereas the latter lives on through a vertical slice and a further prototype. 1313, in particular, was a victim of the franchise’s turn towards a mass consumer market and a licencing deal with Electronic Arts: a scruffy, nerf-herding bounty hunter yarn without a cute mascot did not conform to Disney’s standards of merchandising integration, nor EA’s multiplayer mania of the time - which made manifest in a pair of Battlefront titles. Ironically, that Disney and EA would later rehabilitate the brand through The Mandalorian and a single-player experience in Star Wars Jedi: Fallen Order proved that there was a wealth of riches to be extracted from Level 1313.

No, 1313 was not a roguelike through 1,313 levels of Coruscant.

Parsing the Unseen64 archive provides a peek into parallel planes of possibility: a captivating campfire of demos and odd objects. One of my most cherished pastimes is to search by my personal favourite franchises; Crash Bandicoot, for instance, has a number of entrants. In 2010, a game entitled Crash Landed was in development by Radical Entertainment - an auxiliary link leads one to a Crash Bandicoot encyclopedia featuring stills and concept art. Additionally, Renegade Kid delivered an impressive pitch for the Nintendo DS, effectively translating the desired aesthetic of its console kin. Similarly, the Lost Media wiki is an appropriately rich reservoir of all content lost to either entropy or apathy; may Doritos Crash Course 2 live on in our collective cultural memory. However, though this corn chip challenge was once accessible, not all catalogued curios came to life.

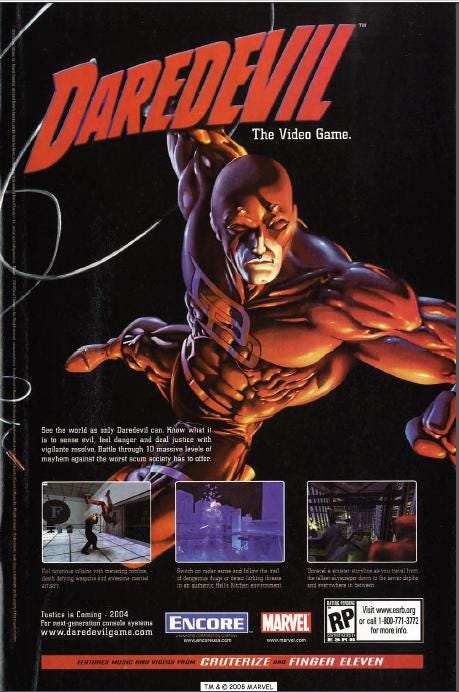

For instance, Daredevil: The Man Without Fear is a perfectly preserved relic of a time wherein Marvel was not the finely tuned, hermetic enterprise it is under Disney’s jurisdiction. On Valentine’s Day, 2003, 20th Century Fox prepared a feast of a feature film within Hell’s Kitchen: a complimentary concept to their burgeoning X-Men universe, further affirming their share of the protracted Marvel canon. Simultaneously, 5,000 Ft. - a small studio known for porting the Army Men series to the PlayStation 2 - were enlisted to deliver a low-budget adaptation of Daredevil’s most memorable moments exclusively for the aforementioned platform. Under a pact with Encore, Inc., who had reserved the rights of a few notable Marvel characters, the studio would digitise ten of Matt Murdock’s non-litigious skirmishes - as indicated by a rogue advertisement.

If this advertisement made it to print, not even Daredevil could have sensed his game to be in danger of cancellation.

As Fox’s Daredevil drew closer, 5,000 Ft. were encouraged to expand their ambition, thus raising the profile of the character across mediums. Ultimately, the team would begin working on a cross-platform, open-world brawler, experimenting with Daredevil’s signature echolocation and … Tony Hawk-style grinding? The latter was a request by Sony themselves, presaging a crisis of identity that would eventuate in a reversion to its linear origins. Twenty years later, however, a prototype would escape from the bowels of Hell’s Kitchen, conveying the pulpy panache of the character in a manner tantamount to The Incredible Hulk: Ultimate Destruction. In this era of licenced titles, there was not a unified philosophy to their means of adaptation. Before Ultimate Destruction, Hulk (2003) was a contained brawler with stealth segments as Bruce Banner; ironically, Batman: Dark Tomorrow gave way to a brighter future for its hero’s adaptations.

Today, the regard of franchise fare within the medium has evolved from cynical means of merchandising to mature, integral propositions. There is a sound apparatus around these properties, either through vertical enterprises in Warner Bros. or partnerships with Triple A houses. All of our entertainment has become centralised and consolidated; an independent studio in the vein of 5,000 Ft. would not have a chance to pitch their vision to Marvel Studios. Though this may make for polished, sleek product, it can cause acute creative malaise. Rocksteady’s reward for producing the most influential comic book trilogy of its industry was to surfeit Warner Bros.’ appetite for live-service revenue. As they were bought by the Bros., they could not take their wares across the pond and set up shop on a Daredevil adventure. Our current anti-competitive model may have momentarily imbued these titles with a commercial safety net, yet it has become a perilous web of micromanagement and exorbitant profit margins - as indicated by Insomniac’s required sales to turn a profit on their coming slate of Marvel games.

Still, we are no closer to a Batman Beyond adaptation.