Celebrating twenty years of Half-Life 2: how Valve's sophomore campaign forever changed the industry

Embracing Steam's power in an age of discs consolidated their nascent empire; Source's sophisticated physics raised the studio a generation ahead of their rivals.

In an age where Valve were known for their voracious appetite for innovation, rather than a benevolent regent presiding over the preeminent platform for digital distribution, the most impressive Washington monuments were known to emerge from their northwestern compound, rather than the capital itself. Their debut record, Half-Life, bore a scope challenging contemporaneous first-person shooters, emphasising mechanical minutiae and environmental storytelling rather than raw rampaging through horrendous hoards. Charting the crumbling hallways of Black Mesa unveiled a cosmic conspiracy, blending the pulp lore of Area 51 with a genuine respect for the player’s physical relationship with the space. Assuming the role of Gordon Freeman - a civilian scientist, rather than an adept marine - Valve designed perplexing puzzles to counterbalance combat, sanctioning an experience that unveiled itself in real-time, rather than deferring to cutscenes to convey action.

Save for its conceptual triumphs, the default keyboard binding of WASD emerged as a universal standard of control - drawn from Quake, yet codified through their stride. Nevertheless, their pioneering of emergent storytelling did not solely settle upon single-player titles: their proprietary GoldSrc engine would inspire a pair of paradigmatic multiplayer titles in Team Fortress and Counter-Strike. Both were devised as mods for Half-Life - their teams were hired by Valve to be officially incorporated under their brand. The former would receive a sequel that has persevered for a peerless period of seventeen years; the latter’s direct sequel - primarily in name, admittedly - is one of the biggest games on the planet. Team Fortress’ bespoke classes gave a greater sense of character to cooperative battles, whilst Counter-Strike’s clear objective imbued its combat with a simple, yet urgent vocabulary: either plant the bomb, defuse it, or wipe your enemies out.

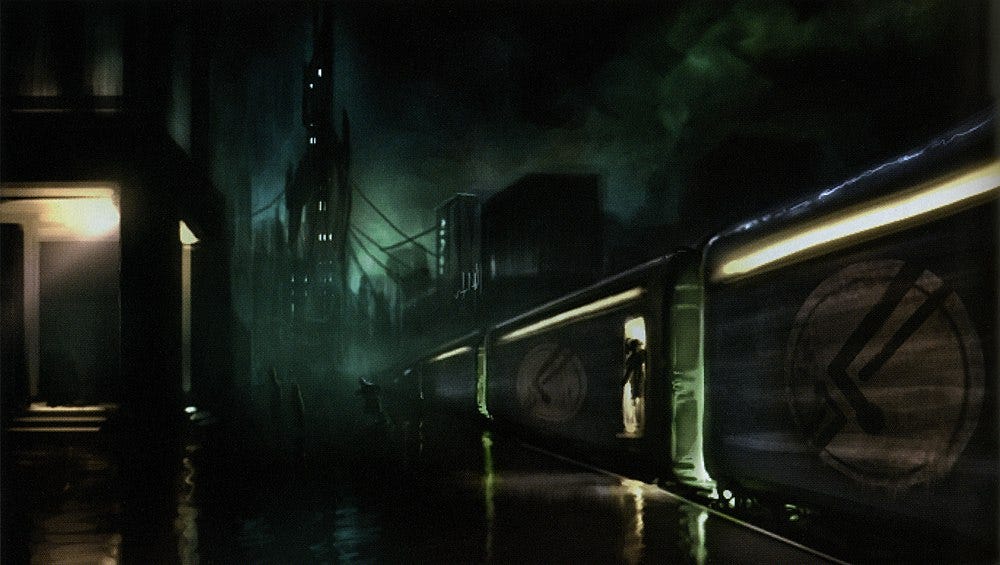

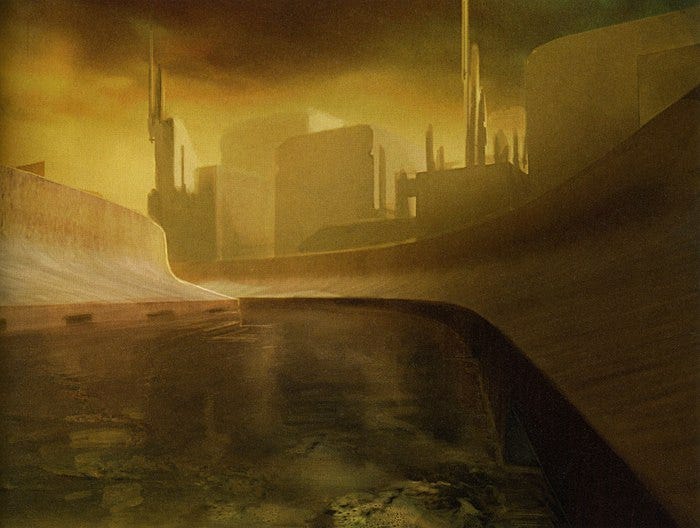

However, their finest work would emerge through Half-Life 2 - though not the one residing within your Steam library, rather its troubled development. On October 2nd, 2003, Gabe Newell - the president and co-founder of Valve - discovered that the bare code for his studio’s Source engine was compromised; five days later, an early build of Half-Life 2 leaked onto the internet. Newell turned to his community to uncover the culprit, culminating in the arrest of twenty-year-old German hacker Axel Gembe; his intrusion caused damages in excess of $250 million alone. Gembe’s mere curiosity, rather than malicious intent, motivated his efforts - regardless, the FBI and German police cooperated to limit the damage access to Valve’s systems had aroused. Though this leak would appear close in character to the final, retail product, Half-Life 2’s rigorous revisions became apparent; Valve had experimented with 30’s, 40’s, and 70’s design sensibilities prior to settling upon its ultimate Eastern European tone. Furthermore, residual files served as vestigial indicators of the game’s earliest iteration: a grim, gothic journey through an apocalyptic America, communicated shades of Orwell, Blade Runner, and steampunk.

Concept art for the original conception of Half-Life 2

Valve weathered this intrusion with integrity, delaying Half-Life 2 an entire calendar year. However, a few weeks prior to this incident of force majeure, the studio drew the ire of their community through their atypical approach to marketing the title: Newell had set a steadfast release date of September 30th, 2003, in spite of universal insistence that it would not be ready in time. Against a demonstration of its design at May’s E3, where press were not permitted to physically play the game, skepticism enveloped engagement. The meagre measure of time before its formal debut did not appear to be particularly promising; its inevitably delay did not receive an updated release window in return. Consequently, Gembe’s hack was both an aftershock and part of a sustained tremor - by March 2004, however, Valve managed to recuperate and produce a fully playable Alpha.

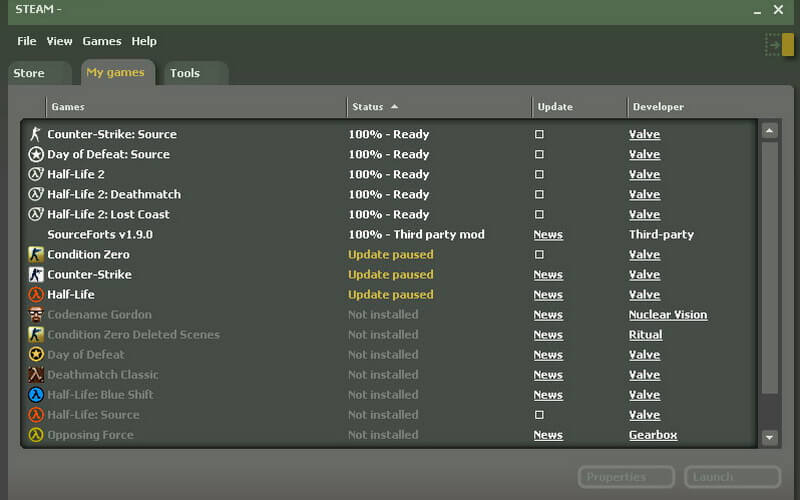

In tandem with this tumult, Valve had launched Steam - their own private platform - to provide their consumers with ease of access to their proprietary titles. Steam would help regulate anti-cheat measures and update games automatically; players found it to be rather curt, instead. Steam demanded a constant internet connection, a challenge to the 80% of its American audience who could not access a broadband connection. Furthermore, its obtuse interface and hampered download speeds drew blistering malcontent - the days of democratisation in server browsing seemed to have ended. Curiously, when Half-Life 2 carved a niche for itself on store shelves, consumers were required to verify their purchase through Steam. Indeed, its selection of CDs had to be explicitly read by Valve’s software, instead of being implicitly granted by the goodwill of your hard-earned.

How Steam appeared in 2003: leaner and greener, featuring Valve’s suite of first-party titles.

Consequently, at the end of its rocky road to release, audiences expected an experience shattering the very paradigm of play itself. Granted, wily pirates had an indication of its ambition; those without a sound internet connection or moral apprehension were denied insight for some time. Ultimately, its reception was rapturous: superlatives flew with abandon, heralding the arrival of a mechanical messiah - per PC Gamer. Critics and consumers alike were taken by its physics alone; players were empowered through a novel Gravity Gun to heighten their haptic relationship with the medium itself. Objects buoyed themselves in rippling waters depending upon their weight; characters articulated themselves with minute modifications in expression. For the entirety of the storyline, you inhabited Gordon Freeman, beginning with a powerless procession through City 17 leading to a pulsating escape: from its besieged rooftops to the alien sludge of its sewers. Accompanied by an intuitive, intelligent partner in Alyx, Freeman would be charged to curry rebellion against the inhuman Combine - by buggy or boat, zombie haunt against treacherous road trip.

To this day, Half-Life 2’s polish is paramount to its appeal. Beginning with the halting musings of the benign G-Man, its subsequent story has a particular air of portent; its minor moments of reprieve emerge through its sombre character moments. Citizens within City 17 are kept under an existential model of oppression, weathering Combine intrusion with indifference. The potency of its presentation is in its canny interpretation of a power fantasy, foregrounding the conversation between scripted setpieces and player input. After a rigorous campaign leads the primary party to the Combine’s Citadel, G-Man strips agency from the player, placing Gordon Freeman in suspension amidst the wanton chaos. Ultimately, we are at the whim of an inconceivable power, playing a fluxional role in a conflict with interdimensional implication. That we can remain in a fixed perspective for the entirety of the storyline and succumb to forces we cannot control challenged the conditions of the form itself.

Half-Life 2’s confident art direction appears ageless; its aesthetic principles underpinned a contemporary VR experience in Alyx.

Valve time has become a known metric throughout the industry. The studio operates on their own terms, outside of the typical commercial concerns of its contemporaries. In the years after Half-Life 2, licencees gradually assisted Steam in becoming a storefront, rather than a server for Valve’s own titles. Therefore, Half-Life 2 presaged an online environment wherein physical shelves were analogue measures of storage: is it not much easier to have a digital library kept in the cloud? Against early concerns of ownership being taken from the player - an unintentional echo of Half-Life’s binding thematic tie - Steam grew to foster live relationships with its players, later introducing a Marketplace that evolved consumer’s wallets from fixed to flexible; hats for Team Fortress and knives for Counter-Strike became means of currency unto themselves. Valve slowly cultivated a language for its community, as it once did for the first-person shooter genre writ large. Though its monopoly upon distribution can be argued against, the quality of its product is superior to its contemporaries - both in its library and its social elements.

With regard to the Source engine - the basis of Half-Life 2’s technical triumphs - its potency has endured as a democratised tool of development. Garry’s Mod, a serialised sandbox built upon this foundation, allows players to toy with the physics, articulation, and environments inherent to the Source engine - particularly in its biblical library of third-party curios. Moreover, its robust toolset has served as a reliable means of animation; a notable portion of YouTube creators have their origins in capturing the oddities of GMod’s cinematic properties. Conversely, conventional titles came forth from Source, both within Valve and the greater modding community: the Left 4 Dead and Portal diptychs were founded upon the engine, whilst DOTA 2 was conceived as a Source remake of its original WarCraft III mod. Though a successor to Source was introduced through their inaugural VR title in Half-Life Alyx, later adopted by Counter-Strike 2, its legacy lives on through GMod’s persistent popularity and Apex Legends - albeit on a technicality.

The broad canvas of Garry’s Mod, the crafty composition of Portal, and the cinematic fervour of Left 4 Dead were achieved through the Source engine.

Ultimately, in both a philosophical and commercial regard, Half-Life 2 is the most crucial title of its time. Through its conceptual considerations, developers were challenged to evolve the medium to a more immersive end, though without compromising the textural vitality of robust physical relationships. In its debut on Steam, however, publishers were charged to either work with the pioneering platform or start one of their own; the latter often resulting in a return to the former, as in the case of EA and Ubisoft. Though Valve have yet to produce a third instalment - not only for Half-Life, but for any of their brands - the rich lineage of titles inspired by its revelations has helped to elevate the industry in esteem. Now, I wonder what Alyx’s ending indicated?

Half-Life 2 is available for free on Steam until November 19th. All future purchases will include Episode One and Episode Two with the base game.